Wes Anderson's History without Historicism

The Phoenecian Scheme, the colonial fiction, and the Art of the Deal

An idyllic Levantine landscape unmarred by the traumas of the 20th century, Che Guevara serving as the personal guard of a European billionaire, dethroned Egyptian princes in three-piece suits, a French colonist donning a symbol of resistance against French colonialism.

Wes Anderson’s images, aesthetic, humorous, and colorful, are mere fetishes, erasing all substance from its symbols, depicting history devoid of historicism.

The Colonial Fiction

The film’s Levantine setting, or at least a fictional reimagination of the tumultuous region as Modern Greater Independent Phoenicia, is presented as a singular, sovereign entity suspended in a liminal temporal zone situated between the pre-colonial and post-colonial, a continuity without the ruptures of world war, empire, and decolonial struggle. While Anderson extensively employs colonial iconography in the movie, he completely erases the salience of these symbols, reducing imperialism to mere aesthetic texture rather than historical structure.

The Fez

Anderson refuses to depict any explicit form of colonial violence. In fact, the film’s depiction of the world is peaceful and adamantly cosmopolitan.

What traces of violence remain, such as the mention of slave labor and famine, again, take the place of background texture, never visualized or interrogated. The result is an aesthetic (of colonialism) that flirts with barbarism but never confronts its implications. Violence, when it appears at all, is depicted as the sporadic whims of eccentric individuals, the corrupt businessman, and the communist revolutionary, removed from their historical and structural contexts, removed from cause itself. In this sense, the film collapses the political into the psychological and erases the structural contradictions that birthed these conflicts in the first place.

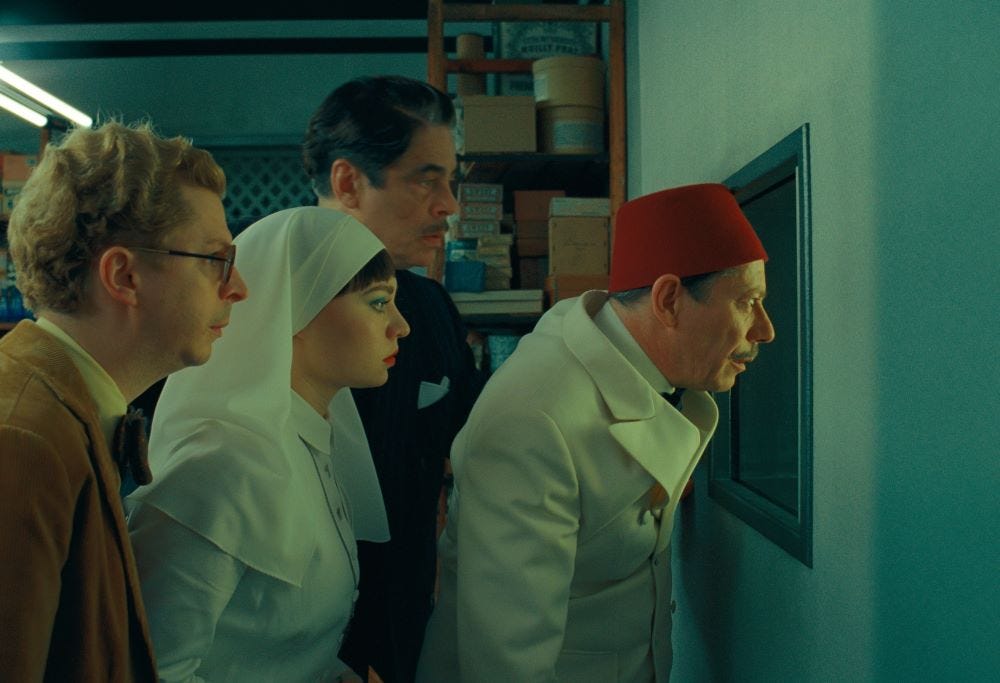

Yet despite the absence of history, the film remains saturated with its style: fashion, architecture, and lingo. Prince Farouk, a parallel to Egypt’s last monarch, wears a Western suit, signaling assimilation into European modernity, while the Western characters don the Fez (Korda, an Armenian, and Marseille Bob, a frenchman, a highly ironic choice as the Fez was a symbol of protest against french occupation in Morocco ), a headwear deeply associated with Ottoman identity and colonial mimicry. Historically, the Fez was adopted by colonial elites, then discarded in post-colonial nationalist movements. Its reappearance here is not innocent. The Fez now functions as a symbol of colonial nostalgia, as Tanjil Rashid noted in their review of the film (which to an extent inspired this one) in The Guardian (Rashid 25), emptied of its political content but loaded with pure aesthetic value for consumption. The inversion, where the colonized elite wears the West and the westerner wears the Orient, reenacts a fantasy of cosmopolitanism that is built upon, and blind to, histories of domination.

The film’s use of these symbols within a supposedly “post- (or pre-) racial,” apolitical world amounts to a visual revisionism. By stripping them of their historical significance, Anderson presents empire not as a system of exploitation but as an apolitical style. The viewer is invited to consume colonial signifiers as timeless and quirky trinkets rather than cultural artifacts anchored in oppression. It is the cinematic equivalent of displaying a swastika purely as a Buddhist symbol, technically accurate, yet morally and empirically evasive.

The Phoenician Scheme, then, constructs a kitsch aesthetic of colonialism: a world where the symbols of empire survive, but the violence that made them legible has been erased. The result is an apolitical fantasy, an orientalist dreamscape without conquest, a sovereignty without struggle. What remains is not history, but an archive of imperial nostalgia, curated without context and consumed without consequence.

Railroads

The Phoenecian Scheme inserts itself into the wider colonial fiction through its depiction of development led by a white European businessman. The titular plot is, in reality, a massive infrastructure and industrialization project in what would have been European colonial territories. The film juxtaposes its depiction of desolate desert and forest landscapes, unmarked by the touch of civilization, with pockets of modernity (always surrounding European characters), culminating in what the billionaire protagonist Zsa Zsa Korda calls “the first abstract representation of modernized Phoenecia”, a massive three tiered statue consisting of rail roads, a giant dam, factories, and other marks of (distinctly european) industry.

The colonial revisionist movement propagates the narrative that colonialism benefited the global south (much like how slavery apologists assert the same for the enslaved). The pre-colonial state is often described as a backwards, stagnant, and Hobbesian relic of the Middle Ages, waiting for the material and cultural enlightenment that colonisers would eventually offer. The movie’s telling of Korda’s plans for Phoenecia, then, is essentially a sanitized retelling of this narrative, in a more Rousseauian pre-colonial context, and without the blood and racism.

Railroads, ubiquitous in these narratives, including the film, are demonstrative of this revisionism. They are often cited as an engine propelling the barbarous indigenous towards modernity. Colonial apologists point to the indian railway network built during the British Raj as evidence that the legacy of colonialism is one of technological and economic advancement. This account is wrong on two counts. For one, colonies are often de-industrialized, with their pre-modern industries (silk and textiles in India, for example) violently dismantled and replaced by the business of providing raw materials for the imperial core. Railroads, symbolic of this transformation, are not built for the sake of economic prosperity but systemic extraction. Rather than accelerating progress in colonies based on traditional craft and industry, colonization involves a structural transformation of the economy to serve the needs and profits of the imperial elite. Thus, whilst superficially the empire brings modernity to its colonies, it ultimately serves to extract both labor and material value from them without any compensation. Secondly, the focus on colonialism’s material legacy willingly neglects the very real suffering experienced by colonial subjects. Again, in India, culture was suppressed and erased, traditional class and ethnoreligious divides were radicalized and weaponized, leaving ideological scars still felt today. Authoritarian bureaucratic management caused the death of millions through mismanaged public health and food supply, exemplified by the disastrous Bengal famines.

In the movie, railroads are both an instrument of economic and cultural advancement. They are integrated within the process of industrialization, and their construction even conveniently involves the liberation of slaves owned by a local monarch. Thus, it simultaneously perpetuates both sides of this revisionist narrative. What’s more, the famine in the film, presented in narration but never in image, is shown to be the consequence of personal whims instead of structural consequences. This verdict could be applied to most of the film, where personal impulse materializes miraculously in reality, sporadic, not immoral but amoral, condemned only playfully and humorously.

The amorality of actions taken by the protagonist Zsa Zsa Korda is a reflection on our numbness to the crimes of capitalists in reality. Corruption, violence, apathy, childishness are the norm, accepted, bland, and an ever-present fixture in the background of public consciousness, while generosity and moral action become spectacle, both in fiction and reality, both Korda and Bill Gates. Amorality is no longer condemned, as punishment for capitalist elites has become merely symbolic gestures without substantive consequence. Generosity and moral action are celebrated, but lack an antithesis. The films continues this tradition of structural doomism by making Korda’s road to moral redemption a completely personal journey, not one where the established villain is brought to justice by a hero or his victims (it was quite obvious in the film that Korda can never be held truly acountable for anything), but one where he sees the light through family, religion, and charity, but ultimately his own desperate circumstance.

Capitalist Redemption

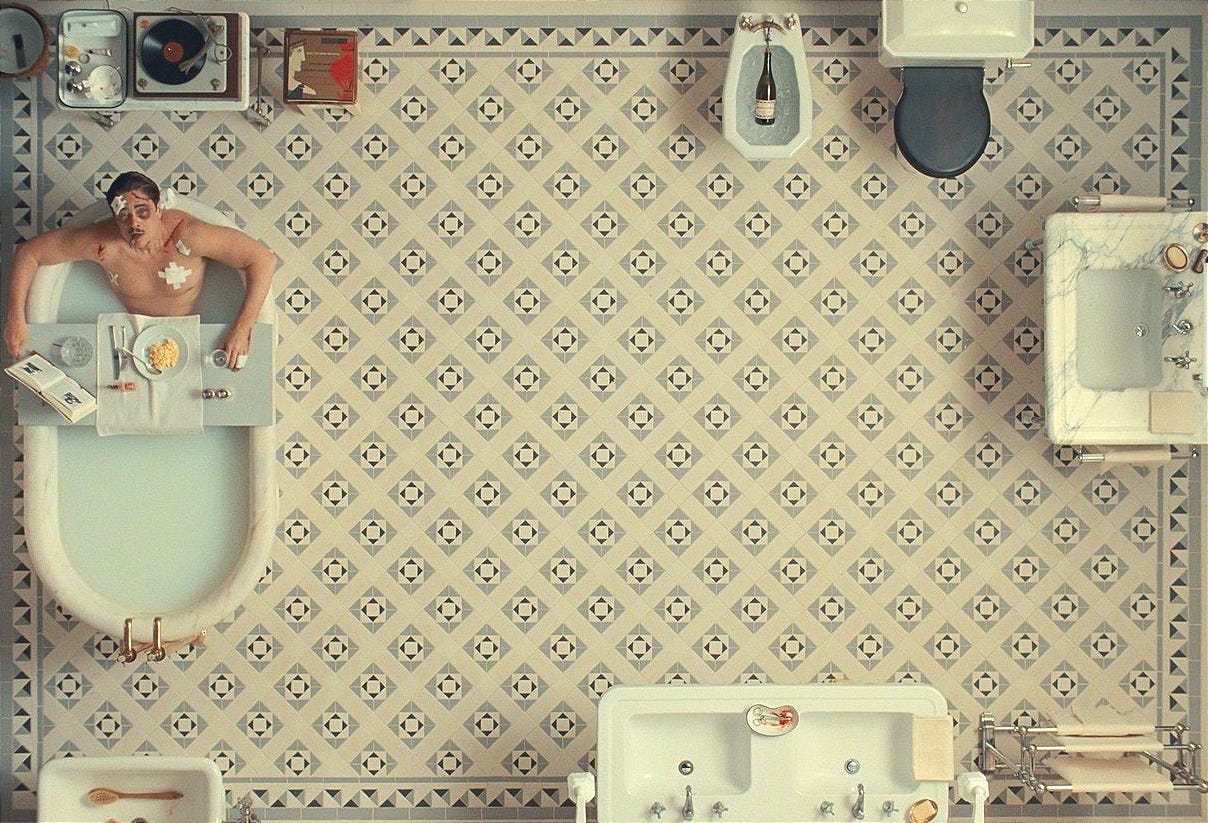

The spiritual arc undertaken by Zsa Zsa Korda in The Phoenician Scheme mirrors, bizarrely, that of Emmet in The Lego Movie. Both protagonists begin as alienated subjects suspended in liminal, depersonalized worlds. Each character is estranged from their environment, unable to see their consciousness reflected in their labor or its products—a condition Marx defines as the essence of alienation (Marx 1844). Their initial existence is marked by compliance, repetition, and social detachment, symptomatic of a capitalist order that renders labor external and meaningless. But both narratives resolve this alienation through what Marx considers the ideal of labor: creative, self-directed activity that transforms both the world and the self. For Emmet, this means his evolution from a reified worker-drone into a “master builder,” liberated from the instructions of capitalist command. For Korda, it is a transition from an empty, despised billionaire to a humble chef, whose craft offers him a clichéd but symbolically rich peace. In both cases, labor ceases to be imposed and instead becomes a vehicle for self-realization.

Where the parallel ends, then, is the identity of these two characters at the two ends of the spectrum of capitalism, the worker and the owner. While Emet’s journey to emancipation as an oppressed worker is a commonly explored subject in fiction, Korda’s arc remains rather more complex and perplexing. On the one hand, the depiction of the alienation of capitalists is necessary in constructing a holistic view of the faults of the capitalist system, but this depiction borders more on a glorified retelling of liberal communism than any structural critique of alienation.

Art of the Deal

In classic Anderson fashion, the adult characters in The Phoenician Scheme are rendered rather childish and immature (but this film lacks the antithetical prodigious child to complete the contrast that is present in many of his other works).

One of the film’s elements I wish to draw attention to is its depiction of the act of conducting business negotiations. The surrealism and absurdity of their depiction satirize corporate formalities playfully, though again, without much consequence.

These scenes begin with a statement from Korda along the lines of “all terms have been agreed to, this meeting is merely a symbolic confirmation of our cooperation”, paired with the offering of a hand grenade as a greeting gift the, civility is upended by the other party’s outrage upon discovering Korda has been “fiddling with it.”, then voicing their decision to withdraw from the contract. The meeting then degenerates as the two parties yell intelligibly at each other, ending when Korda challenges the other party to some game, violent confrontation, or gimmick that would win their cooperation, whether it be basketball, bomb threats, or marriage.

In a film “about a family and a family business”, very little business is actually conducted. The satire is obvious, legible, and digestible, but fails to yield any substantive critique of the practice of doing business. Does it demystify the act of deal-making, which the current US president is so fond of glorifying? Or does it depict this absurdism as tragedy, grown-up man-children playing with the fate of the world?

The answer is neither, because again, the story takes place in a pastel colored world devoid of stakes. The consequences of these negotiations appear to be solely personal for Korda; thus, their absurdity only acts as comedy, not tragedy. Unlike its parallels in reality, politicians and businessmen boasting about their prowess in cheating each other, which results in bombs being dropped, workers being fired, people dying, and descending into poverty, the film’s portrayal of business is simply silly.

A Peaceful Life

The film concludes with Korda becoming temporarily destitute, choosing to start over as a chef and open his own restaurant. On the surface, this appears to resolve his alienation through creative labor, echoing Marx’s notion of work as a medium for self-realization. However, this resolution is ultimately structured meritocratically (Liesel says in the film, “My father’s entrepreneurial spirit did not dim“). Alienation is not overcome collectively or structurally, but individually, through entrepreneurial reinvention of the self. The message, at its core, is this: to find meaning in a world devoid of community or justice, one must rediscover the self through ownership and artisanal labor. This is not a critique of capitalism, but its sublimation. Fulfillment is still possible, not by challenging the system that alienates, but by mastering it aesthetically. In the end, Korda does not transcend the logic of capital; he re-enters it under the illusion of autonomy, cloaked in the romantic fantasy of the small business owner.

This directly contrasts the ending of The Lego Movie, which depicts liberation as a collective effort that freed every individual from both the structure and ideology of capitalism through the literal destruction of the order, symbolized by the film’s main antagonist, Lord Business. The logic of capitalism itself is abandoned by the working class in this context through the abandonment of instructions (the Lego version), which used to dictate every aspect of life.

In comparison, Anderson appears to be adamantly pro-establishment, peddling a fantasy of fulfillment within the logic of capital, not through its abolition.

Bibliography

Rashid, Tanjil. “The Phoenician Scheme Is Fantasy. It Is Also a Remarkable Engagement with the Real-Life Conflict in the Middle East.” The Guardian, 17 June 2025. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/17/the-phoenician-scheme-is-fantasy-it-is-also-a-remarkable-engagement-with-the-real-life-conflict-in-the-middle-east.

Marx, Karl. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Translated by Martin Milligan, edited by Dirk J. Struik, International Publishers, 1964.